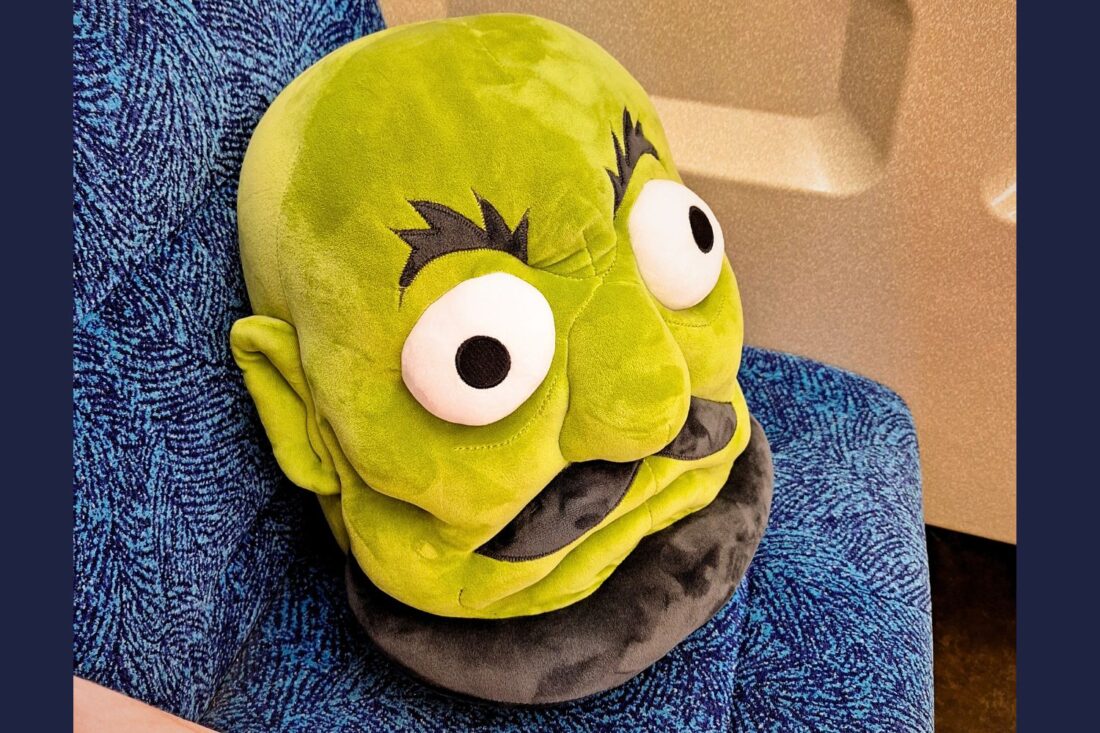

I disembarked from Fujigaoka Station, weighed down by enormous, colorful shopping bags, and carefully placed my new companion on the seat beside me. It is rude, of course, to occupy any seat on the train with one’s possessions, but my friend was quite large and the train was quite empty. An older woman across the aisle smiled indulgently at my companion, as though he were a cooing infant.

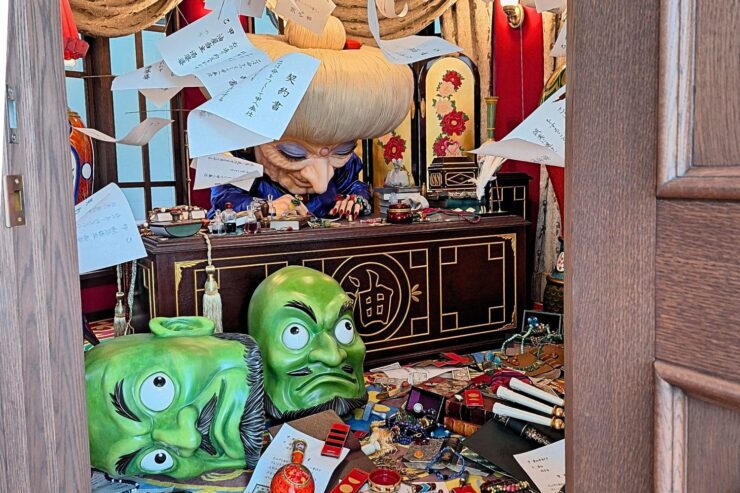

I get it. I felt the same way when I chose him from among the other exclusive plushies at Ghibli Park’s Grand Warehouse. My companion, a life-sized recreation of one of three kashira, the bouncing green monster heads that guard the chambers of the sinister bathhouse keeper, Yubaba, in the Miyazaki masterpiece Spirited Away, gave me one wall-eyed stare in the gift shop and it was over. I wasn’t going home without him.

Though toting him around the park for the rest of the day wasn’t easy, his weight was lessened by the reactions he received from passersby. Who would have thought that a monster’s bearded, disembodied head would inspire heartfelt gasps of “Kawaii!” and glances of envy?

Well, a Ghibli fan would have thought. Because isn’t that the most Ghibli-esque of notions? A person steps into a fearsome, strange world, only to be overwhelmed by affection rather than fear.

When Pigs Fly

I have rarely been called pretty as often as when I wore a mustache, pig nose, and sunglasses to Ghibli Park. The reaction from fans and staff made me wonder whether I should wear a snout on the regular. A too often unsung Ghibli masterpiece is Porco Rosso, the story of a disillusioned Italian pilot turned bounty hunter cursed to look like a pig upon losing all faith in humanity. As a former cosplayer, I was never going to not wear something, and at least the Porco Rosso accessories were easily removed when I got fed up with them. (Maybe that means that my own faith in humanity can be removed and restored at will.)

On the recommendation of a Japanese acquaintance, I arrived at the park early and lined up outside the gates of the newest park area, the Valley of Witches. When the gates opened, I hustled over to Howl’s Moving Castle and, falling prey to fangirl inclinations, squealed with joy at the sight. I was especially eager to lay eyes on the recreation of Howl’s iconic bedroom; fellow depressive maximalists know well that the moping wizard’s absinthe-green-tinged room, cluttered with mobiles and dusty treasures and mechanical tchotchkes and two little plushies is aspirational interior design. Alas, as I presented my ticket to the castle attendee, I learned the painful truth; sadly, I had not purchased a premium ticket and would be denied access to Howl’s beautiful squalor-nest. Was I a little crushed? Obviously, and damn me for a fool for not reading the fine print when I bought my tickets.

As a girl, I adored the works of Diana Wynne Jones, particularly the Chrestomanci books and The Dark Lord of Derkholm. As an adult, Ghibli’s adaptation of Howl’s Moving Castle feels more cathartic with every rewatch. Sophie Hatter, who learns to believe in herself only after she is transformed into an old woman, is among the best of many wonderful Ghibli heroines. Many women relate to Sophie’s glorious liberation; the revelation that becoming less conventionally attractive means becoming less constrained by others’ expectations is, arguably, one of the best aspects of growing older. Relatable, too, is Sophie’s practical approach to dealing with a supposed heart-eating wizard after she realizes he is no more threatening than a tantruming toddler, a manic-depressive mess who was never taught to take care of himself. “How terrible, there’s a heavy weight in my chest,” Howl complains, as he learns to be a better person. Sophie knows this already: “A heart’s a heavy burden.”

I resigned myself to exterior castle photos and then comforted myself with a visit to Gütiokipänjä, a recreation of the charming bakery from Kiki’s Delivery Service. Japan takes baked goods seriously, and my enormous cinnamon roll did not disappoint. Neither did the cozy, vintage decor inside the bakery, which indulged in the kind of sly sapphic energy Ghibli sometimes teases us all with. A poster of a girl eating a tiny piece of fruit from a woman’s hand read: “The forbidden fruit is the sweetest.” Look, witches are totally gay and that’s awesome and Ghibli knows it, though they may never admit it directly.

After the bakery, I was magnetically drawn to the carousel. Now this is a magnificent thing, offering rides aboard a whimsical collage of characters and devices spanning decades of Ghibli lore. I bought my ticket for a thousand yen and then waited only a single ride for my turn. The decision was daunting. Did I ride aspiring aviator Tombo’s propeller bike, or dare sit on Moro, the fearsome wolf goddess who raised the human girl San in Princess Mononoke? Nah, who the hell am I kidding? Throughout my childhood in northern Michigan, I dragged a raggedy Dakin deer plushie with me wherever I went. I was fated to ride Yakul, because he is the best boy, the courageous and loyal elk who braves banishment and fearsome monsters alongside his rider, Ashitaka. The most coveted seat for park attendees, many of whom dressed as Kiki, was a flying broomstick. For those with refined tastes, the Witch of the Waste’s palanquin offered a more dignified ride.

As the carousel began to turn, a sudden bout of dissociation descended on me and my noble steed. I felt, suddenly, very ridiculous. Here I was, an adult woman and solo traveler, wearing a pig nose and mustache and riding a fantasy creature in circles. I had no family or children to make faces at on the sidelines, and I clung briefly to my carousel pole with sudden shame. But then a family of strangers waved at me, and I waved back, and the moment passed. Every Ghibli character has felt displaced at times, and the magic of these stories is that people find themselves again in the displacement and are often better for it. I never want to be the kind of person who does not ride a carousel. I, like Sophie Hatter, am too old for nonsense.

Worlds Within Worlds

Ghibli’s Grand Warehouse requires a separate, timed ticket in order to avoid overcrowding, and I was compelled to the gates at 10am. My favorite area within the warehouse was dedicated to The Secret World of Arietty. Underrated among Ghibli canon, the 2010 adaptation of Mary Norton’s The Borrowers lovingly reimagines the mundane world from the perspective of a miniature family. This isn’t just Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, fun and nostalgic as that movie may be; the difference, here, is that Arietty and her family live and build their entire lives underfoot, trying to avoid the notice of humans. In the Warehouse, visitors are allowed to experience what this might be like.

The flowers were towering, but so was the refuse left behind by giants. Children posed for pictures inside an abandoned glass jar. A giant plastic soy sauce fish adorned a wall. Dewdrops the size of billiard balls, staples as long as my hand, a matchbox the size of a backpack, all lovingly recreated. It was charming, but it was also a reminder of the debris people create every day. Arietty and her family, in true Ghibli fashion, exemplify making the most of an environment and its resources, fully embracing the old idiom about trash and treasure.

As a resident of Japan, I know you can get a photo with No-Face anytime and with less hassle at the Donguri shop in Osaka’s Shinsaibashi PARCO department store, so I did not wait in that epic line. Instead, I took my time admiring an exhibit on the food in Ghibli films. The meals depicted in virtually every movie were on display, accompanied by animation cells and sketches of the meals in storyboard form. The aperitif in Porco Rosso, Kiki’s chocolate cake, the buffet-turned-trough where Chihiro watches her parents transform into pigs. The realism of the model dishes is unsurprising. In Japan, hyperrealistic acrylic fake food displays called shokuhin sampuru are standard at most restaurants. Ghibli never forgets to feed its characters.

Speaking of food; although there were a few restaurants in the Ghibli areas, I didn’t eat at them. A Hawaiian culture fair was taking place in the middle of Moricoro Park, which contains more than Ghibli Park. I picked up loco moco at a food truck and sat on an astroturf lawn to enjoy it while a live ukulele talent competition show carried on onstage. Ghibli Park merging with an existing greenspace by building upon the former site of a city expo is very on-brand. Miyazaki has championed environmentalism for as long as he’s been creating; his iconic post-apocalyptic manga and pre-Ghibli film, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, is a desperate plea for maintaining the balance between humanity and nature.

After lunch, I went to Mononoke Village. Of all the different areas in the park, this one is the most disappointing. The ethereal ancient forest atmosphere, inspired by the southern Kyushu island of Yakushima, is so tangible in the movie but doesn’t exist here. Given that there are actual forest groves in Moricoro Park, this did feel like a missed opportunity. The mosaic-tiled statue of the boar god Nago is also a slide that kids can enjoy, but there are no glowing rattling kodama, no illuminated, antlered forest gods. There is hardly even a recreation of Irontown, apart from a single building that offers a uniquely hands-on park cooking experience. Then again, I did enjoy roasting gohei-mochi over charcoal, slathering it with walnut miso sauce, and devouring it under an awning.

I sipped Ramune with my disembodied monster head at my side, then left the area. Outside, I was delighted to see a catbus trolley passing by; the most glorious of golf carts, the Ghibli Park catbuses act as a mobility aid for those who need it, or affordable transport for those who are tired of walking. In addition to the catbuses, I noticed an elevator labeled Lift For Witches in the center of Valley of Witches. Again and again, I saw attempts to make the park as welcoming as possible.

Valid complaints have been made about Ghibli Park’s recent increase in ticket prices. While an adult can visit the park on a limited ticket for just 1000 yen (about $7.00 USD), and a child can do the same for just 500, a premium ticket is a different story. Before the park opened, limiting attendance was a deliberate choice, intended to ensure the park was accessible to people from all walks of life. They wanted to mimic the cost structure in the same way they have always done for Ghibli Museum Mitaka, which regularly welcomes school field trips. But Ghibli is still a business, and given the high demand for tickets, any company would charge more for unique attractions beyond the entry price. I did not have a premium ticket. Did I enjoy the park less? I’m not sure, because I had a ton of fun regardless.

At times it felt obvious that the park’s lead director was not Hayao Miyazaki, but his son, Goro, who has consistently failed to live up to the standard set by his father. While this statement seems loaded, it’s the truth; with the exception of From Up on Poppy Hill, the films Goro Miyazaki has helmed for Ghibli have received negative reviews from fans and critics. A Ghibli devotee would question, then, why so much of the Valley of Witches is dedicated to what is inarguably the least beloved Ghibli movie, 2020’s Earwig and the Witch, Ghibli’s only disastrous foray into CG animation. Why did Ghibli Park, which opened the Valley of Witches later than other areas of the park, try so hard to shoehorn elements of a widely-disliked film into the popular park rather than, say, putting more effort into incarnating Mononoke Village?

Ghibli Park, which will celebrate its second anniversary in November, is very young. Theme parks always evolve. Time will tell whether Ghibli will address any of its missteps. I do not dare to dream that anything related to a friend’s favorite film, When Marnie Was There, will ever feature in the park, but who knows? The park is in its infancy. And if the studio’s future remains uncertain, at least the Ghibli backlog is entirely rich with possibilities.

Ghibli Heaven, Ghibli Hell

In the warehouse, after viewing the food exhibition, visitors are led down a long, impressive hallway lined with posters of every Ghibli production. Grave of the Fireflies, My Neighbors the Yamadas, Whisper of the Heart, Pom Poko; even the titles that have achieved less international fame inspire gasps of delight and nostalgia from park attendees. My little revelation in this hallway was a newfound appreciation for the source materials Ghibli chooses to animate. In addition to boasting unparalleled heroines, Studio Ghibli has adapted more works by women writers of SFF and children’s lit than any other operation I can think of, including books by Diana Wynne Jones, Ursula K. Le Guin, Mary Norton, Eiko Kadono, Aoi Hiiragi, and Joan G. Robinson.

Given such a legacy, a general sense of awe (albeit a little coerced) comes naturally to Ghibli Park. The actual magic of the place is how easy it is to feel immersed in a tiny bit of the Ghibli world, however fleeting that may be. Before the park opened, a friend who adores the attractions at Universal Studios and Disney told me he expected little from Ghibli Park: “It’ll be good, right, but it won’t be what it could be if someone else were designing it.” His words reflect what some visitors, especially those from abroad, have observed: Ghibli Park, devoid of rollercoasters and log rides and the usual amusement park costumes and performances, “isn’t really a theme park.”

Well, to that I say, “Thank fuck!”

You never encounter a crowd of bodies pressed around Donald Duck, never have your irises seared by visions of a breakdancing Darth Vader. The odds are against anyone vomiting, and bathroom lines are nonexistent. You aren’t likely to get bumped into anywhere but in the tempting gift shops, outside which people queue up in an orderly fashion. You can walk up a random staircase at the back of a nondescript building and find yourself in either Kiki’s bedroom or a little witch-themed bookshop. And it will sound like a lie, but I swear on my green monster son’s head it isn’t: I spent 8 hours at Ghibli Park and only heard a child cry once.

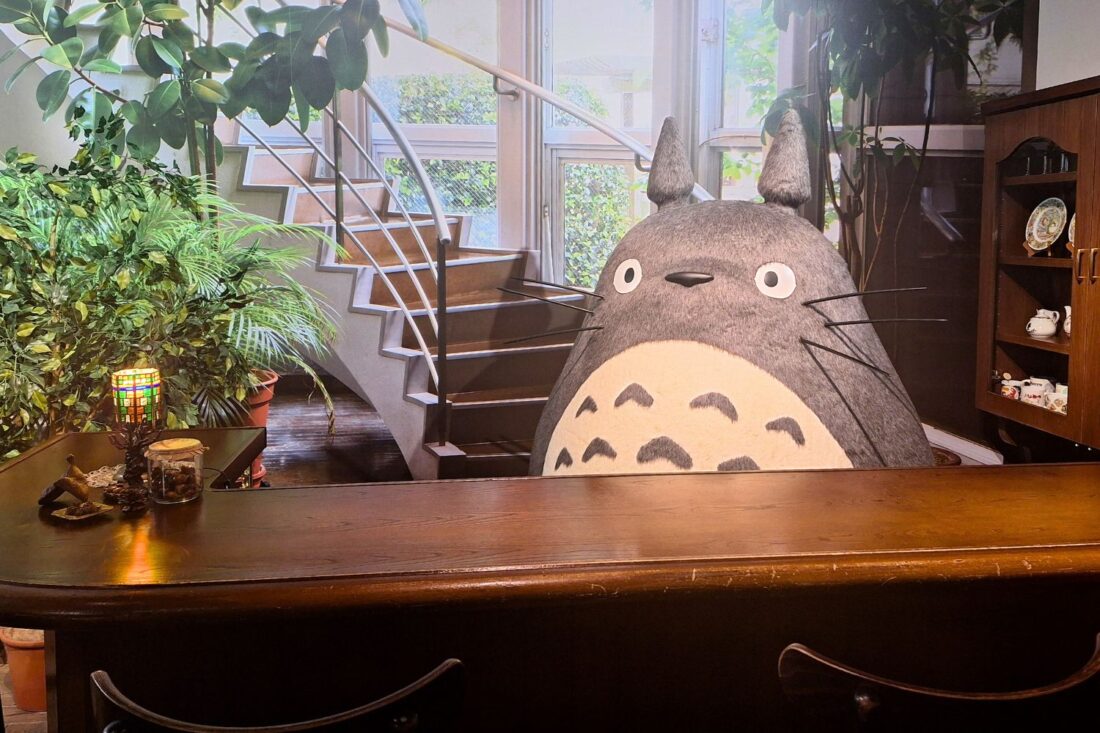

I did have one strange, uncomfortable experience when I made my little pilgrimage to Dondoko Forest, Ghibli Park’s homage to My Neighbor Totoro. Getting to Dondoko Forest requires trekking a kilometer away from the rest of the attractions, either along paved roads or, preferably, by way of a verdant path through the woods. This area is remote enough that more people cough up the yen for the catbus trolley or use Moricoro Park’s transit service to reach it. To find Totoro, explorers must climb a tall flight of stairs reminiscent of those that lead to temples and shrines. At the top of the forest stairs, surrounded by trees, the cuddly giant awaits. Totoro!

Or, rather, a wooden Totoro-shaped play-structure called Dondoko-do. Nearby, a booth sells Ghibli charms that mimic those sold at Shinto shrines, such as embroidered omamori, and wooden ema (prayer plaques).

A little blonde girl, obviously American like me, was glaring at the booth as I reached the little summit. She was shouting at the park attendees and employees, seemingly furious. “Pray to one god!”

I used to live in Nevada and visit Utah. This uncomfortable experience was unexpected, given the setting, but not at all unfamiliar. Most parkgoers ignored the outburst entirely. Immediately, the girl’s parents hushed her and hurried her away, as if they had nothing to do with their child being so deeply indoctrinated at such a young age. I felt a pang in my heart, some weird combination of anger and pity. Imagine being a child visiting a beautiful green grove occupied by one of the most wonderful, docile fantasy creatures ever invented, and finding the experience threatening.

This fundamental failure of outsiders to understand that reverence is not the same as religiosity is something I have encountered at various points while living in Japan. While certainly, many people hold religious beliefs and superstitions here, the definitions are far more accommodating than many Western religions are accustomed to. Treating a Totoro statue like a shrine isn’t sacrilegious. Besides, I’d argue that Totoro has brought more joy to people than most deities. It ain’t that deep, and it ain’t that serious. In Japan, anyone can appreciate the beauty of a place of prayer without feeling pressured or ashamed.

I bought a forest-spirit omamori for myself, and another for my atheist father. They were unique, well-made, and possibly a little magic. If this means we burn in Ghibli hell, at least the food will be great.

When I adopted my son of choice, my one regret was that I did not have more yen and more arms, a la Kamaji, to take home all three kashira. In Spirited Away, the three bouncing heads are never separated from each other, and sometimes even fuse into one creature. In every Ghibli film, the protagonist inevitably finds themselves thrown into unexpected circumstances—be it a bathhouse operated by spirits, or an ancient forest populated by sentient insects, or visiting a summer home haunted by their dead grandmother, or accidentally engaged to a cat. Though our obstacles are bound to be a little less fantastical, the overall experience is universal. Anyone who wants to enjoy an interesting life will be required, at times, to step into the unknown and build a home there.

Sophie did it, and Chihiro did it, and Nausicaa did it, and Ashitaka and San did it, and Ponyo did it, and Sheeta and Pazu and Mahito and… well, all of the Ghibli leads. And if even I had to do it, moving alone to Japan in my thirties, then I think my solitary kashira can do it too.

Have you been to Ghibli Park? What Ghibli film raised you?

Also, Halloween draws nigh! To commemorate spooky season, next time I’ll be writing about body horror and queerness in a groundbreaking manga, The Summer Hikaru Died, but other series likely to be referenced are the works of Junji Ito, Parasyte, To Your Eternity, and Hell’s Paradise.

In this article: In the US, Max (HBO Max) has streaming rights to all Studio Ghibli titles.

Up next:

- The Summer Hikaru Died (Kadokawa Shoten/ Yen Press, 2021-) First four volumes published in English.

- Parasyte: The Maxim (Madhouse, 2014): Available on Crunchyroll and Netflix.

- Hell’s Paradise (MAPPA, 2023): Available on Amazon Prime and Netflix.

- To Your Eternity (Brain’s Base, 2021): Available on Crunchyroll and Amazon Prime.

This seems to be a shared world anthology.

Fortunately, not the world we actually live in which, as Steven Pinker has so brilliantly shown, gives us many reasons to be hopeful about the future.

One problem with this review is that it’s obvious that the anthology is coming from a particular point of view, but that point of view is never stated. I’m assuming from the title that it’s coming from the hard Left, but titles have lied before. I’m going to assume that my assumption is correct and not buy the book. But I might be missing out because the review left the issue up in the air and I had to assume.

Why am I skipping it? Because there’s a whole bunch of good books out there, so I have to filter the pile somehow.

#2 FCoulter, what modern SFF authors do you consider “right-leaning”? (I define “right-leaning” as favoring the general political and economic policy wishes of the current Republican party.) I can’t think of any off-hand, beyond some of the the sword-and-sorcery and military subgenres authors. I would classify most commonly anthologized writers as “left-leaning”, “neutral”, or “implied politics not relevant”.

@2 — You can find out more here:

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/561572/a-peoples-future-of-the-united-states-by-edited-by-victor-lavalle-and-john-joseph-adams/9780525508809/

It’s presented as literary and speculative fiction; the dread word science does not appear.

Amusingly, the publisher tries to make the book sound more optimistic than (judging from the posting above) it actually is.

@3 – There is far more to political thought than the simplistic Left / Right spectrum. The fact that you think the only alternative to the Far Left is being a Trump supporter concerns me. For example, there’s a very strong libertarian strand in Science Fiction. If this is new to you, I suggest you look at the nominees and winners of the Prometheus Awards. You’ll probably recognize some of the names.

Here’s a link to the winners – http://lfs.org/awards.shtml ; I’m sure that you can find the various nominees; the LFS doesn’t make it easy to find them. (Perhaps by browsing the blog or press releases?)

@@.-@ – According to the Press Release, the book is

The problem is that oppression comes from all sides of the political divide, not just from the Right. But if the book is only dealing with oppression from the Right, it’s not one that I’m interested in reading. Too many blinders in the book’s conception.

It sure looks like that’s what the book’s basis is, but I could be wrong. Which is why I’m bringing it up.

@5

Sounds pretty libertarian to me.